Colonialism does strange things to a culture. Ignoring one’s own indigenous “ordinary” culture, and blindly imitating others’ “legitimate” culture is one of them. It takes years and a lot of efforts before a culture realizes its self-worth during the post-colonial journey. At present, urban culture in India and Indian diaspora around the world is undergoing this journey. Let me share some of my life and thoughts with you as a rural folk artist from India who, first, migrated to a city in India and then to California.

I was born in a small village called Samai-Khera in the Bharatpur district of India’s Rajasthan state. Samai had around 500 families and a population of around 2,500 people. There was no electricity in the village, and we had to walk for five to six miles to reach the nearest bus station. Our house was made of mud and reed. I remember it was a beautiful house. As I slept on a charpai (wooden Cot) under an open sky in front of our mud house, my grandfather used to narrate stories of kings and princes to me. Staring at the Milky Way, I used to be transported to a different world. Other stories I loved to hear from my grandfather were about Nautanki. Nautanki is a North Indian folk musical theater art form. Until a few decades ago, it was the most popular form of entertainment in rural north India—even more popular than Bollywood (Indian film industry). My grandfather told me that my father grew up to become one of the biggest Nautanki stars in India. Through my grandfather’s stories, my father became my biggest hero. I dreamed of becoming a great singer like my father, to be worshipped by audiences like he was, and to be on the top of that stage called Nautanki.

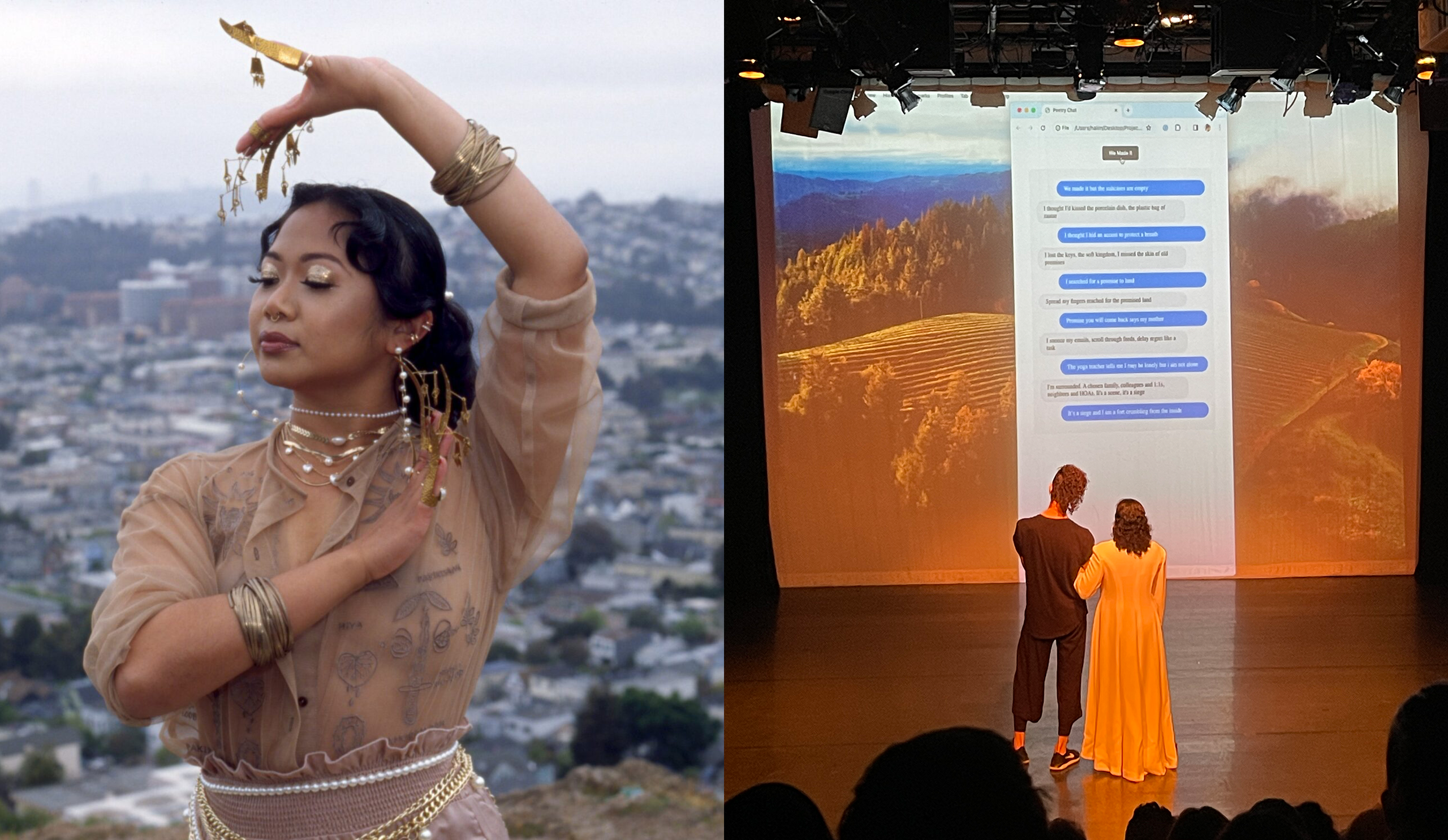

Devendra Sharma performing in the Nautanki "Amar Singh Rathore" with his father and renowned Nautanki artist and guru, Pundit Ramdayal Sharma

Let me share my first Nautanki experience with you. That night, I was attending a wedding in Mudhera, a small village in the Bharatpur district. I was eight years old. While playing with the other kids, I overheard that a Nautanki troupe had been invited to perform that night, and my father was going to make an appearance as the star performer. Although I had heard that my father was a big Nautanki performer, I had never seen him perform on a Nautanki stage in a village. I got very excited keep awake until the Nautanki started. As the night approached, thousands of people gathered in the vast open grounds in front of my grandmother’s home. Many of them were coming from adjoining villages, on foot and in bullock carts with sturdy bamboo sticks in their hands. People were taking their seats on the bare ground and getting ready for the performance. Suddenly, there was a commotion in the audience. I heard people shouting that Master Ram Dayal ji had come. Seeing me, my father hugged me as he always did. I was so happy. I could not believe that I was the son of this big star. My father arranged for me to sit on the stage itself. The harmonium player started to play nagma (the melodious compositions played on harmonium to set the audiences’ mood for the Nautanki performance) and the sharp, loud sound of the nakkara (percussion instrument composed of two drums played by two wooden sticks. This instrument is unique to Nautanki. It is so loud that it can be heard over many miles. It serves to “advertise” Nautanki) reverberated through the whole village. People were sitting on the ground, on their bullock-carts, on tractors, on roofs of houses, on walls, on platforms in front of their homes, and some were even hanging from trees. They were talking to each other, laughing, sharing jokes, smoking, eating, drinking chai (tea), and doing other activities. Hundreds of people would occasionally shout a jaikara (a slogan spoken in a chorus) of Giriraj ji or Krishna ji (our local deity)—“Bol Giriraj Maharaj ki Jai!” (Praise Giriraj!). The atmosphere was electrifying.

A religious Nautanki in progress in the holy Indian town of Vrindavan

Finally, the Nautanki performance started at around 11 pm. I was mesmerized as soon as it started. I had not heard such melodious and powerful singing before that night and never did after that. Over the years, I have heard thousands of film songs, classical and semi-classical compositions on the radio and television, and attended several live concerts, but they pale in comparison to the wonderful opera that I heard that night in Mudhera. As the night passed, the performance got even better. At one time, people were so absorbed in the performance that there was a pin-drop silence. Imagine that in a crowd of thousands of people! Many times during the performance, I had goose bumps. It was so good! The Nautanki “Indal Haran” was performed that night. The audience participated in the performance in many ways. For instance, some audience members were giving spontaneous cash awards to performers after well-sung pieces.

The performance finished when the sun rose. The story of Indal Haran had concluded, but the people were not ready to budge. They requested one song after another from my father. My father obliged them as far as he could. Then he requested the audience to let the performers get some rest after singing the whole night, and reminded the audience that they also had to get back to their villages and get on with their work. I noticed that my father had a tremendous clout over the audience. Whatever he requested, they accepted. Reluctantly, the audience agreed to my father’s advice but demanded a final romantic number from him and the heroine of the Nautanki, a famous female artist named Prem Lata. After that song, the performance finally ended. Surprisingly, even after being awake the whole night, I was not feeling tired. I wanted the performance to go on like the other audience members.

- Devendra Sharma portraying the character of Sultana Daku in the Nautanki “Sultana Daku”

While growing up in New Delhi, India, I noticed that most people in the cities looked down upon rural, ordinary culture. The middle class people in cities imitated the people in the upper classes, who in turn imitated the West and their erstwhile English masters. Most city people have not seen an Indian village. They think about Indian villages in exotic terms and although they consider the rural arts to be heritage that should be preserved, in their day-to-day lives they entertain themselves with Hollywood and Bollywood, Monet and Picasso, Elvis Presley and the Beatles, and so on. Other city-based elites listen to Indian classical music. Growing up in a city, I felt culturally disoriented among these people and found them hypocritical. When I migrated to California, I found the same attitude among most people in Indian diaspora. Either they did not know about Nautanki at all, or they had misconception about it, leading to a condescending attitude towards traditional folk arts such as Nautanki. I wanted to show them the real power and genuineness of indigenous entertainment forms. I wanted to show that ordinary rural art compares on an equal footing with “elite” art.

Another reason for this desire was that I had started writing new Nautankis with my father on social issues such as dowry, women’s empowerment, environment protection, and family planning. He wanted to make Nautanki contemporary. I regularly performed in these Nautankis with him and found that audiences took a keen interest in them and discussed these social issues during and after the performances. I want to now use Nautanki as a medium for bringing contemporary issues concerning the Indian diaspora to the fore.

My father and I also started an organization called “Brij Lok Madhuri” to create and perform Nautankis and other folk performances on social issues. The Government of India and a few international institutions such as Johns Hopkins University hired our organization to create folk performances in India and train other troupes to perform them. These field-based experiences showed that Nautanki and other similar folk forms were highly effective in communicating social messages, especially among rural audiences. As a communication student at Ohio University, I explored how these performances encouraged a community feeling and how they affected their audiences.

As a Nautanki artist, I want to explore the potential of this art form. My father and I have had numerous discussions about the place of folk forms like Nautanki in a cosmopolitan, global society. I perform Nautanki for personal satisfaction as well as for the betterment of artists and audiences of Nautanki and many other similar folk forms around the world. I also perform Nautanki to bring attention to contemporary and controversial issues of today.

Devendra Sharma as Sultana Daku, the fierce bandit who fought British in the early 20th century

For the Performing Diaspora festival, I would present a half-hour Nautanki piece in the traditional Nautanki format that concerns a contemporary and controversial social issue. Today, there is an increasingly common phenomenon of Indian men who come to America to study or work but go back to India and get married there either because of parental pressure or to get a big dowry (cash given to the groom’s family by the bride’s side). Many of these men leave their wives in India and lead separate lives in America, where they often have another wife or a girlfriend. Their wives in India do not see them sometimes for years, and are crying for them. Because of societal constraints, they can neither divorce their husbands nor have sexual freedom. To make matters worse, the society leads women to blame themselves for their husbands’ lack of interest in the relationship. The Nautanki script I am creating critically examines this issue. It will be an entertaining and thought-provoking musical theatrical piece.

Participation in the performing diaspora program is providing me the valuable and much-needed support and resources to bring attention to the indigenous art of a disempowered culture to the diverse audiences of the bay area. Thank you “Performing Diaspora”!

Share This!

More Good Stuff

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF

Wow! What a captivating and transporting story! This is such important work, and we’re thrilled to watch it develop at CounterPULSE!