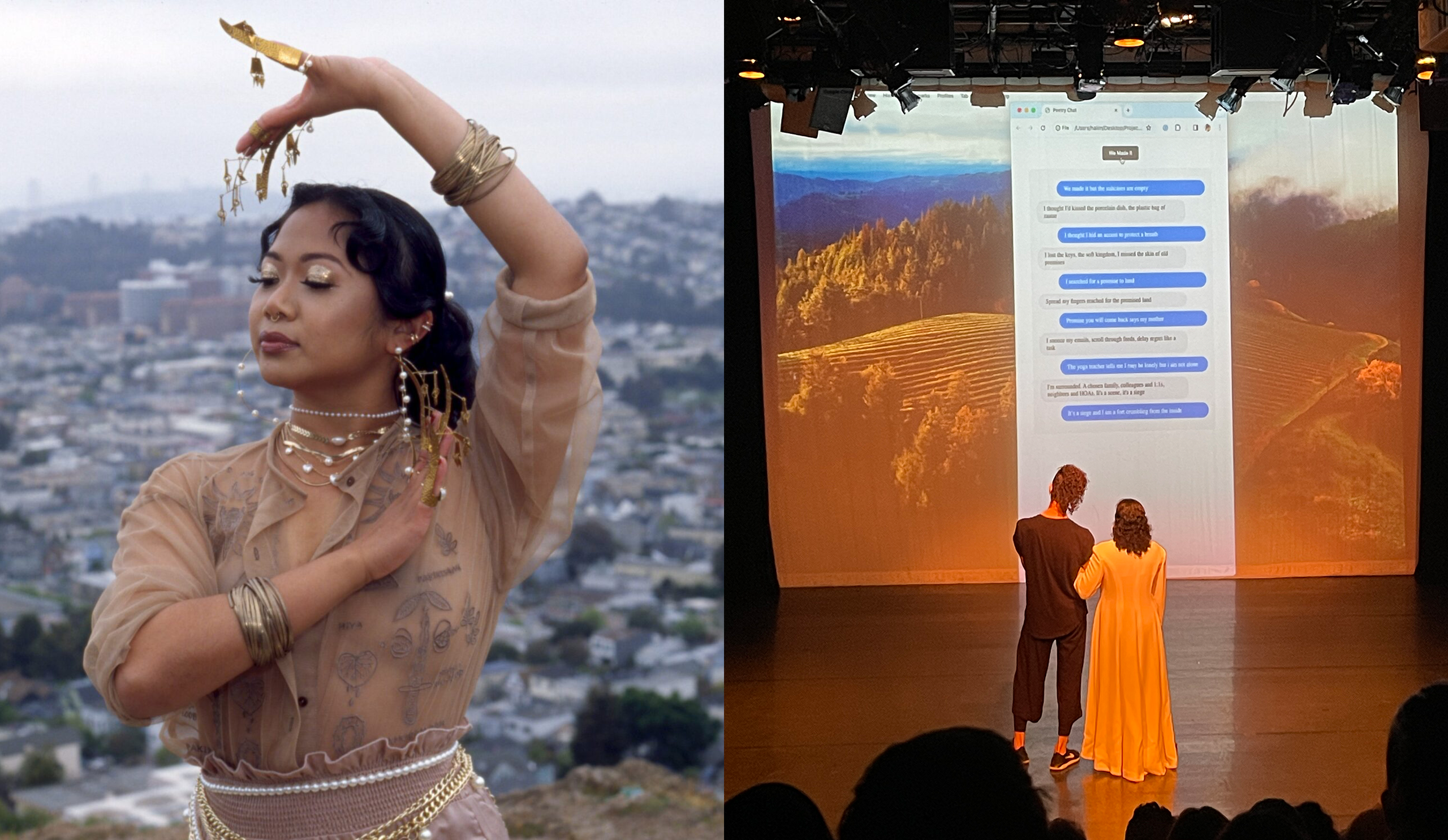

I am a world choreographer originally from Indonesia and trained in the classical and traditional forms of Java, Sunda, and Bali from when I was a child. The essence of the esthetics of Indonesian dance, and that particularly from the islands of Java and Bali, can be explained through three words: wirama, and wirasa. Wirama means the harmony and internal rhythm of the movement. Wiraga is the intensity and fullness of the movement not in term of its external power, but more along the lines of being filled with chi (in Chinese) or prana (Sanskrit). Soft and delicate movement can be wiraga while movement that is seemingly strong and powerful can lack it altogether. Wirasa is the feeling of the movement. The word “feeling” here is used not in sense of emotion or passion, but in term of the sensation when emotion and mental construct are set aside.

My interests, however, go beyond the set traditional and classical pieces to developing new choreography using traditional and classical technique to explore issues of concern to the community. This interest forms a natural continuum with my native tradition. For example, in my original culture, narratives from the Mahabharata have long been adapted in Wayang (shadow puppet theater, for example) to explore issues of family planning, tolerance, and democracy.

Part of the challenge for traditional art forms is to remain fresh and relevant while at the same time remaining true to their roots but not simply repeating the classics and relegating the art form to dry, museum pieces. In my view the way to meet and overcome this challenge is not to reject new technology or methods as necessarily “corrupting,” but to think clearly about the core, underlying esthetics principles in the tradition.

Of course, a challenge is that for audiences that are not familiar with the tradition, they do understand the structure of the tradition and so anything that has elements of the tradition cannot be innovative. Or, sometimes promoters and producers of traditional dance do not want anything that has a tinge of innovation in it. As a result, many world choreographers I know sell the same piece as both squarely traditional (for those who want it to be so), and also sell the piece as modern/post-modern (for others who want that).

A number of years ago I was backstage with my dancers at a dance festival putting on costumes and getting ready for our performance of my choreography, Remembering. As we were doing this, a dancer from another troupe came up to us and asked, “So, are you doing that ethnic thing?” I was a little surprised by the question, but realized later that all sorts of genres were performed at that festival: ballet, post-modern, jazz, and so on. The dancer who asked the question was being friendly enough and perhaps just trying to figure where we fit in. The next year, I was invited to perform at a second, different dance festival. I sent a video of Remembering to the second festival’s committee, to show them what I was going to perform. A week later I got a call from a nice, but nervous artistic director who said that while she liked the piece, “it wasn’t ethnic enough.” Same piece, ethnic and not ethnic enough.

My experience in this isn’t unique, of course. Dancers from all sorts of traditions that are not necessarily well known get pigeon-holed as ethnic because of their technique. At the same time, however, as “ethnic” or “world” dancers the expectation is often that they work in “preservation” mode, repeating their classics over and over again. Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with preservation. Preservation as such is important, but it is a starting point. It is a starting point so that dancers and choreographers can master technique that takes years to learn, and technique is the departure point for expression. Many choreographers such as myself do perform “classical” dance, but their own choreography is not classical as preservationists would understand it. Nor is it “modern” or “post-modern” as people generally understand the terms and the meaning of modernity.

Share This!

More Good Stuff

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF

Wow Sri,

I think you have really touched on the core motivation behind this entire project. I know internally we are struggling with similar questions, especially in how to present this amazing new work you are all doing to the outside world. Unfortunately, at times in today’s world I feel like publicity becomes an effort to over-simplify and I applaud our publicity team for not settling for that. From my perspective, I am really to eager to see how each of you addresses this concern. I see it as a great way of helping these traditions to evolve. After all those traditions had their own beginnings and growth and I see the work that you are all doing, not as creating a new art-form all together, but in owning the traditional in your own way while ushering those traditional forms into the modern era. I certainly don’t think anyone is eager to abandon these “ethnic” performances but at the same time those artforms need the space (and encouragement from artists like yourself) to breathe and grow.

I’m still trying to wrap my brain around wirama vs. wiraga vs. wirasa. Though I love the concept and am eager to see if I can incorporate those ideas in some way into my own creative work. I love those concepts that are both simple and complex, that is what art is is it not? But I think it is something I need to experience first hand rather than simply read about, I’m definitely looking forward to the Works in Progress showings.

andrew

Thank you Sri for your poignant and thought provoking musings. For me the word “ethnic” directly implies “culture-specific”–from geography to climate, from specific garments of clothing, adornments and shoes to bodily gestures and food, from epic to mundane. I do believe that historically each of the “individuals” practising their traditional “art” brought their own unique spirit and expression to the form. Dance and music, like life itself, are in constant flux and to me what makes a “traditional” form of artistic expression relevant is simply the willingness of the artist to dig as deep as possible from within, remember, honor, and yet remain present and connected to his/her actual life experience.

[…] Sri Susilowati talks about innovation within traditional forms and the “pigeon-holing” of ethnic dance: http://dev-counterpulse.pantheon.io/traditional-dance-does-not-put-the-%E2%80%9Cno%E2%80%9D-into-innovation-wit… […]