When you choreograph folk dance and work to transfer movement from its natural habitat to the stage the considerations are: : Is the representation accurate? Am I being true to the spirit of the dance? Have I accurately reflected the integrity and idiosyncracy of the music, dance and people of that area? As important as these questions are, they are also the very elements that discourage creative evolutions from that dance. Additionally, I have always been keenly aware that , in America, all ethnic minorities straddle two cultures on a daily basis. How well we do this determines our social and economic success. This is the framework for my artistic process. And so it is that when I became interested in how my culture influenced my life and my surroundings, and how that informed my art form I had to learn to give myself permission to have a point of view and to give it a voice through dance. It has been a slow and lengthy process that I still find full of surprises.

Mexican folk dance is very regionally specific, both in music and dance steps. It takes but a few notes to recognize the provenance of a folk music selection. And dance steps have very similar identifying characteristics. And so my early attempts at deconstructing the art form were through mixing and matching the various regional music and dance forms. But the one thing that eluded me was how to connect all of this to my American reality. When I say this I am not speaking of a philosophical connection. This was a rhythmic issue. I wanted to be able to use contemporary popular songs in my work in order to more accurately reflect my reality, but the beat was all wrong for the footwork that I knew so well.

I had sort of given up that this connection would ever happen for me when, in 2003 I heard the music of Quetzal, a Chicano band from Los Angeles. i recognized the rhythms of his music. They were very contemporary, yet, very traditionally Mexican. Musically, he had done what I was trying to do in dance. Thanks to a grant from the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Dance Project, that year Quetzal and I went to Veracruz, Mexico. There the syncopated rhythms of the music are in direct opposition to the very symetrical sounds of traditional Mexican music. In Contrast, the fandango (Veracruz) musician and dancer must be as one. It is not about steps or body isolations, it is about rhythms. The dancer must learn to create his/her own percussive sound and become part of the music by establishing dialogues with the musician(s). For me it was a dual pleasure. Not only did I learn to dominate these new rhythms, I also found the vehicle to complete my personal artistic voice.

When I got the inspiration to choreograph a work based on Rudy Anaya’s novel Bless Me Ultima, I found it very easy to make musical and movement choices. Although Rudy Anaya’s novel was set in post WWII New Mexico, the universal themes within it-coming of age, the straddling of two cultures, and the power of good and evil-supercede specific time and place. So contemporary music, coupled with traditional Mexican music (the straddling of two cultures) came as a natural choice. Likewise, the footwork selections were an amalgam of the various Mexican regional dance styles, coupled with contemporary movement.

The overriding element that specifically dictated what music and what steps to use when and where were the words-metaphors, similes, poetic phrases and descriptions-that begged to be visualized-within the novel. Thus, Mr. Anaya’s description “He drew near and saw that it was not natural fire he witnessed, but rather the dance of the witches,” became the dance I have now entitled, Las Hermanas Brujas/The Witch Sisters, I tried to combine the ceremonial aspects of Aztec movement with that which portrayed the action in Mr. Anaya’s words, thereby honoring the spirit of what he was talking about-ancient rituals in our modern world. The musical selection was an original composition written by a dear friend, Mexican composer Gerardo Tamez, long time member of Los Folkloristas.

Similarly, Mr. Anaya describes Ultima’s arrival into Antonio’s world as a momentous occasion. One that literally shook his world, ” My nostrils quivered as i felt the song of the mocking birds and the drone of the grasshoppers mingle with the pulse of the earth. The four directions of the llano met in me, and the white sun shone on my soul.” Since my earliest days as a choreographer, I was always strongly influenced by music. I think melodies have the ability to give new context to any movement, imbuing it with a meaning well beyond its original intent. When I tried to remember how, as a child, I might have felt like that about some one. no person came to mind. But when I heard the song “No One” by Alicia Keyes on the Radio, I understood Antonio’s feeling the moment he met Ultima. So that song became my musical choice. Once again, I used Aztec movement because, in the novel, Ultima’s arrival in the town had great ceremonial significance. I changed the tempo of the step because the music demanded it and, in doing so, I created a contemporary dance movement that seemed to have hip hop elements. That was pure serendipity. When Ultima enters the stage she is using improvisational Fandango footwork. She is a healer and makes organic choices in order to best suit the environment. However, these choices alter the environment. Similary, the dancer must improvise to best suit her environment. Unlike the other dancers, her footwork makes noise thus altering the sound of the music and the stage environment.

In the two songs that depict a family gathering, I was very aware that in all Chicano family get-togethers there are the very traditional elements that, consciously or not, constantly interact. blend and clash with contemporary life. And I tried to depict that through traditional Mexican folk dance movement interacting with pop music and movement.

Finally, the dance that represents a school yard scene, a very important part of the novel because it establishes Antonio’s standing with his own peer group, I looked for a melody that would allow for dance improvisation, just like the Fandangos in Veracruz. There is a living in the moment quality about improvising that is very childlike and it really helped the dancers access their “inner child.” Additionally, the African based rhythms that we created gave the dance the lighthearted mood we needed as a prelude to the ending.

Throughout the piece I tried to be going towards one direction: The creation of a dance suite that blends the vocabulary of traditional and Indigenous Mexican folk dance, as well as African influenced and European based contemporary dance expressions, the creation of a dance form that could be called Chicano, an American amalgam just like me.

Share This!

More Good Stuff

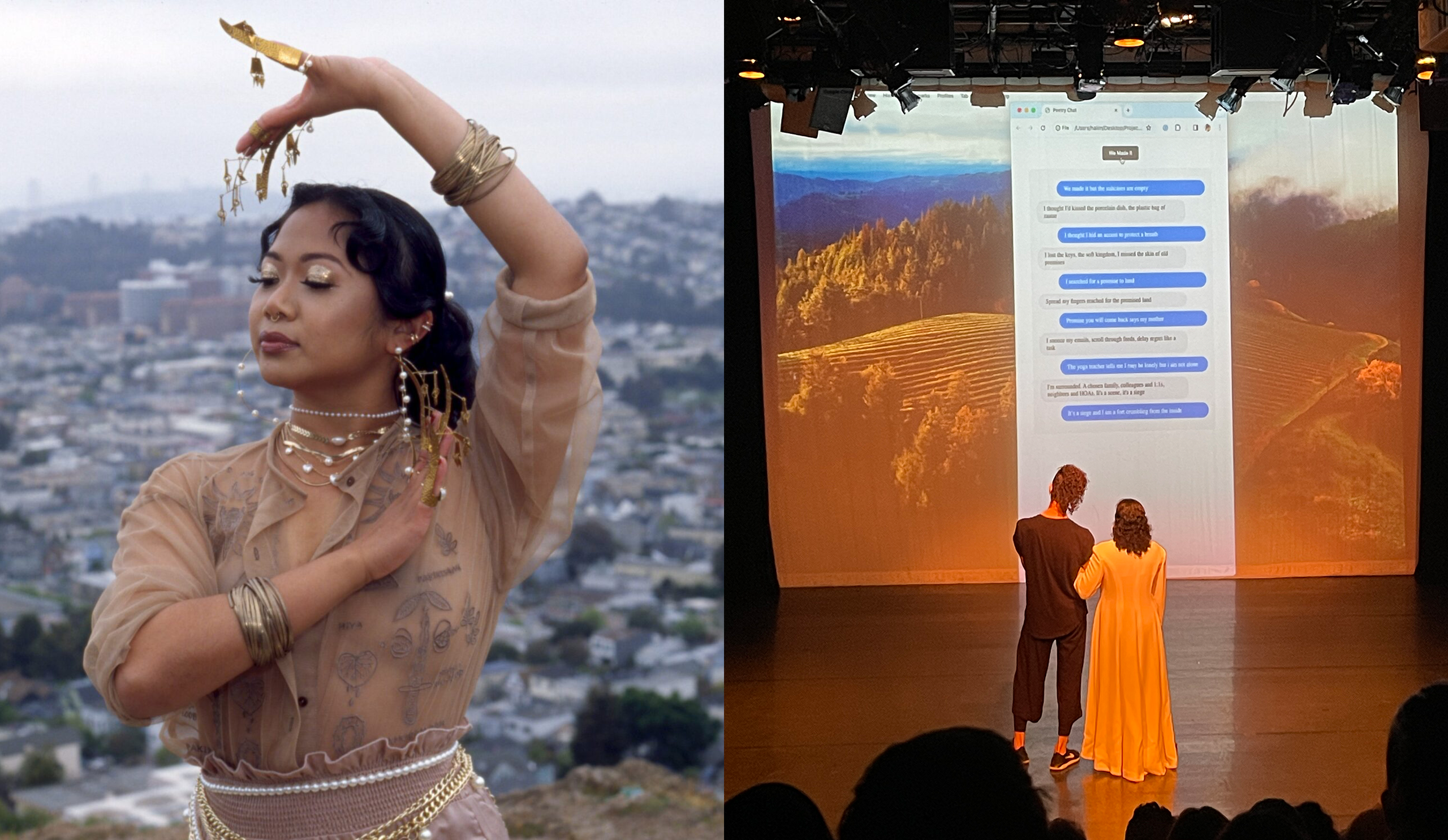

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF

Gema,

Having now seen this piece in its evolution, it’s even more fascinating and poignant to hear this description of your choices. Your daring yet thoughtful choices have translated into a powerful piece of performance!

Jessica