The world is falling apart.

Driven by illusive philosophies, men and women inflict harm upon one another. They destroy fields and forests that give them life; they kill and rape to own land and water. And in their cities they stuff their mouths with a gluttonous rage — only to grow evermore sick and evermore hungry of course.

Seeing this sadness and unhealth, the Gods began to grow anxious. They asked amongst themselves, “How do we give people the opportunity to know truth in a world of money, to experience transcendence in a place where immorality and prejudice is written into law?” They decide to approach Lord Brahma — he who is Creator of the Universe, he in whose hands are the Vedas — and come to the conclusion that human beings shall be equipped with the power of the arts. With these divine tools, they shall know heaven on earth and live reality with each breath.

Lord Brahma compiled this sacred knowledge into a text and appeared before a lone hermit. “Bharata Muni, man of devotion, he who withdraws from suffering! Study this sacred manuscript that was born in the palaces of heaven. In its service you shall find true life!”

Bharata Muni began to verse himself in the secrets of art and theater. He shared his knowledge with his one hundred sons, training intensively for their first performance. Seeing this noble devotion, the Gods sent the dancers and musicians of heaven to impart their secrets upon Bharata Muni. They shared with their human counterparts the sacred musical scales that inspired a celestial peace; they taught the men how to transform themselves into women through costume and movement.

When that fated day of the first performance came, Bharata Muni found that all of the Gods and Demons had come to witness it. He and his ensemble performed a drama that illustrated the Gods’ triumph over the Demons — truth over illusion, good over evil, love over hate. The Demons became enraged and immediately began to voice their anger. They threatened to kill Bharata Muni and whatever mortal dared wield this weapon against them. Fearful for the life of his students, Bharata Muni prayed to Lord Brahma for his protection, who in turn, gave the man knowledge of rituals to be performed on stage that would ensure his safety.

Thus begins the origin of art and theater in the human world.

Sompeah Kru at the Khmer Arts Theater in Takhmao, Cambodia. The bearded mask directly in front of the man in white is that of Lok Ta Maha Eisey; note the four-faced (you can only see two from this angle) representation of Preah Prum or Lord Brahma at the top of his headdress. Photo: John Shapiro.

I wanted to begin this year of Performing Diaspora with an invocation to Bharata Muni, or as we know him in Khmer, Lok Ta Maha Eisey [Grandfather, the Great Ascetic]. It is believed that all knowledge of the arts emanate from this powerful being; he is the ultimate teacher spirit in Cambodian classical dance. Through the loving and molding hands of my teachers, like the hands of their teachers and those before, I am in Lok Ta’s lineage of thinkers and makers, activists and visionaries. It is in his service and our heaven-sent task of inspiring truth and transcendence to which I devote my life and artistic practice.

I originally encountered the story of the origin of theater in Rene Daumal’s Rasa, or Knowledge of the Self and it has since then inspired my way of approaching artmaking. After reading it, I realized my duty as an artist in helping to create a world of harmony and well-being; it reveals the political nature of the theater since its inception. The story ends with Bharata Muni being equipped with the rituals that will keep him safe from harm, rendering the theater as a space to safely share and discuss the ideas, images, and histories that are difficult to approach elsewhere.

For Performing Diaspora, I will be presenting two works from my in-progress Robam Snaih Buon [Dance of Four Loves]. A suite of four short dance works, its uses the human experience of love and Hindu-Buddhist ideas of reincarnation to navigate the terrain between form and spirit, sex and gender while exploring different aesthetic and social spaces and possibilities.

Robam Santhyea Vehea [Dance of Twilight Sky], which opens up the narrative, faithfully employs Cambodian classical dance’s aesthetic and technique, music and costume to depict a homosexual relationship between two divine men. They profess their love for one another; they swear to the clarity of their hearts and marry one another before a liminal twilight sky. Robam Lom Arom [Dance of Emotions’ Caress] follows this euphoric image, depicting a woman named Neang Sovann Atmani who waits by the river at night for the return of her absent husband. She is consumed by her memory of him and succumbs to the phantom weight of its caress in an interdisciplinary world of love and longing, revived outdated traditions and reinterpretations of contemporary practices.

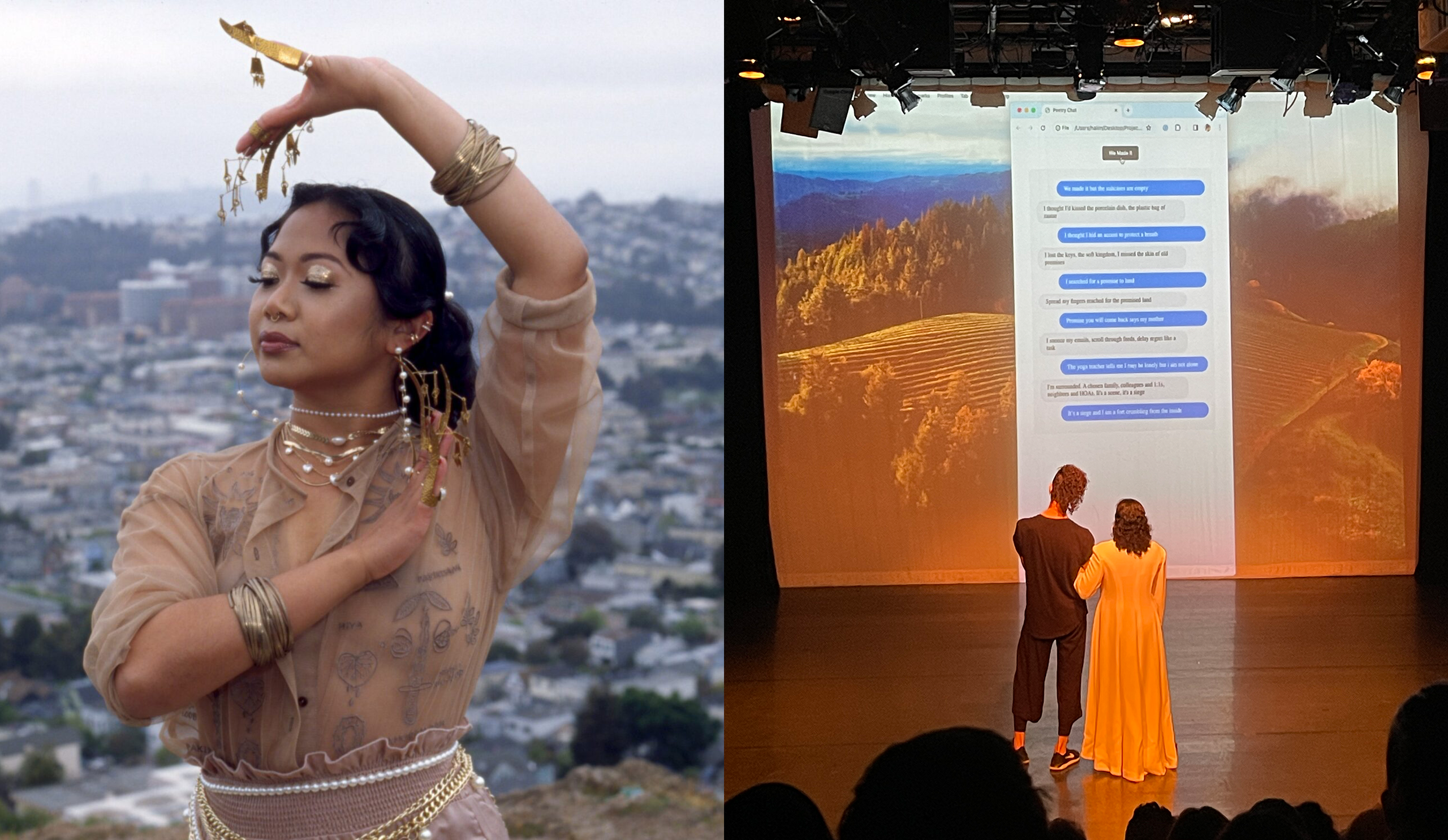

A self-portrait in my old home in Hollywood, half-dressed in a costume for Robam Santhyea Vehea. Photo: Prumsodun Ok.

In Robam Santhyea Vehea, I elevate the experience of homosexual men into the mytho-poetic ritual space in which Cambodian classical dance is set. The dance is performed by two women playing nearong [male] roles as is the tradition. They wear costumes that are physical and visual manifestations of harmony and order — flower motifs that reference mandala that create the overall appearance of snake scales (whose movements invoke the life-giving qualities of water) — thereby suggesting the noble love between two men or two women as being nothing less than harmonious with and in line with divine order. The teacher spirits serve as witnesses to the marriage of these characters and the history they represent; I wouldn’t be here if they disapproved.

Robam Lom Arom, which was originally commissioned by Performing Diaspora last year, breaks away from Cambodian classical dance’s conventions. Movements are exaggerated to mirror the way things become filtered and exploded in memory; the outdated practice of painting the body white is used as a gesture of historical empowerment, ritual transformation, and reinterprets the human body as a canvas for video projection. The unisex elements of Cambodian regalia are removed to leave a spare body and the gendered melodies of the pin peat orchestra are replaced for sound. Although a woman longing for her husband may seem tame as a subject, some in a Cambodian and Buddhist context may consider it as “taboo”. As my teacher suggested, “Well, some people would say, ‘What kind of woman is that? Can’t even control her emotions.’” The oppressive social expectation for women builds itself below and around this dance: a dance where love lingers between bodies once present and physical and in contact that are now absent and disconnected and psychological.

Both of these dances offer challenges to contemporary Cambodian classical dance and performance. They explore and expand upon the form’s expressive possibilities, drawing upon already established ideas to depict subjects that are difficult for others to discuss. For example, when asking a dancer if she would perform Robam Santhyea Vehea with me, she disappointed me with a vague refusal. And after watching a performance of Robam Lom Arom, an arts administrator from Cambodia said to me, “Prum, that was really good. Don’t show it to anyone else though.”

Performing Robam Lom Arom at CounterPULSE in November 2009. Video Still: Loren R. Robertson.

As an emerging choreographer, I could not be in a more difficult space. I have received much funding and support for my work here in California but I have not had the chance to share it in the same capacity for Cambodian artists and Cambodians who — when thinking about the development of the art form — are perhaps the people who need to see it most. The artists that have seen my work recognize the references that I am making, the choreographic innovations I introduce, and the value of my work and voice as an artist and thinker within the tradition. But they all suggest that I keep it hush-hush for my own safety.

Will I be censored if I present my work in Cambodia? Will I be blacklisted? Will the administrative powers in Cambodia make like the demons in the story of the origin of theater and attempt to suppress my voice? Who knows. What comes to mind is the voice of my teacher, so loving and supportive, “You haven’t had any tomatoes thrown at you yet. Why are you scared?”

Equipped with the story of the origin of theater, empowered by the love of my fellow artists in both Cambodia and United States, I join Performing Diaspora once more ready to share my artistry and history. I seek not to create work for stirring controversy but, rather, for the sake of creating a right and just society in line with a divine order. It could not be a more timely moment in California to depict two men marrying one another on the stage; it is my duty to share this alternative philosophy and vision of health and harmony. I am grateful to CounterPULSE and the Performing Diaspora team for giving me this opportunity and pay my respects to them for upholding the purpose and function of the theater since its inception.

Share This!

More Good Stuff

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF