A Cambodian classical dancer, when practicing her moving meditation developed over a thousand years ago as a ritual prayer, displays a serpentine grace that is hypnotic and sublime. Her form is supple, her gestures fluid, and she floats in curvilinear paths across the stage. This is no coincidence as the serpent – moving like the waters that bring fertility and sustenance to the land, bridge between heaven and earth, the being in which the first “Cambodian” sovereign took form (in one creation story anyways) – was worshiped prevalently throughout what is now Cambodia before the introduction of major religions. And today, after many generations of refinement, the serpent can still be seen in this highly stylized art form: its scales transformed into a costume’s detail and its function assumed by a human dancer.

Note the repeating floral patterns that make the dancer a lush and ordered nature - a fertile landscape - with the visual effect of snake scales. Courtesy of Prumsodun Ok.

During the time of Angkor, dancers served as mediums between the king and his gods. Their art and science – harmony in motion, order choreographed, health manifest – was executed to induce the fall of rains that meant survival and vitality for the people. In post-colonial Cambodia (1953 – 1975), the dance form was used as a means of reasserting national identity with dancers playing a pivotal role in reestablishing the sovereignty of the king through domestic and international tours as well as the development of new works. However this creative energy did not last long as the Khmer Rouge, a radical group of Communists who sought to establish an egalitarian agricultural society through the decimation of privilege and culture from 1975 – 1979, brought about the deaths of nearly a quarter of the population, resulting in the loss of ninety percent of artists. The few remaining were faced with the daunting task of reviving a tradition, amongst others, that saw its near extinction under a new government that failed to see its historical meaning: the most sacred works were given socialist embellishments for the sake of performance and transmission and change, no matter how gradual, came to be an enemy of a culture and people seeking stability. Only with the efforts of Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and other forward thinkers has the focus been shifted to creation and development that is natural to any living heritage.

When referring to “her”, I am speaking of an ideal embodied most by the apsara – celestial dancers, the ultimate feminine beauty and grace seen in Cambodian culture and art, the role most young girls in America strive to perform – that I am obviously not. I am a young man performing male and demon roles that are traditionally performed by women. I am a child of peasant farmers practicing an art developed and nurtured in the royal palace (in its more recent history). I wasn’t even born in Cambodia.

But I am actually not that different from my predecessors.

While rehearsing in Cambodia at the Khmer Arts Theater one afternoon, a visiting artist from the National Department of Performing Arts said that I reminded her of Mchas Ksatra Sophilu (His Majesty Prince Sophilu); my refined movements and regal charm took her back to her childhood when she would observe Prince Sophilu dancing in the palace from afar. Chea Samy, the leading performer of female roles during the reign of King Monivong and a key figure in the revival of Cambodian classical dance after the Khmer Rouge lost power, came from the same rural peasantry as my parents. She used to buy white powder with whatever money she had as a child to paint herself and made crowns out of banana leaves – my parents would have said that she was “crazy” just like I was, dancing in my sister’s red dress that looked nothing like the costumes of the dancers performing on the television screen (they were inaccurate as well and reflected a new diaspora community trying to preserve its symbols of culture with tinsel wrapped around hair instead of flowers, paper crowns as opposed to brass dipped in gold, and skirts and bodices that reflect a wedding aesthetic that was immature and unrefined in contrast to dance regalia). I can and will say clearly then – not because of where my parents are from, nor due to the way I look – that Cambodian classical dance is my culture. As a practitioner, I believe fully in its efficacious power in cultivating health and well-being in its audience and environment. I give my life and image to the ideas – knowledge and reason, truth and transcendence, harmony and order, vitality and fertility – and the divine ingrained in and embodied by each and every gesture and detail of this form.

Prumsodun Ok as Prince Vorachhun, manifestation of the earth, at the Red Poppy Art House in San Francisco. Courtesy of Navin Moul.

There are some things, however, that separate me from my predecessors and contemporaries. My artistic practice is interdisciplinary in nature. I am, after all, a filmmaker, designer, and samba dancer as well. I dance as if sculpting light and bending time as any filmmaker does when shaping a light source or editing and infuse my films with the ritualism of Cambodian classical dance. The non-linear nature of time that is evident in filmmaking is something so very clear for thousands of years in Brahmanist thought. And what if films, instead of making you feel sick and anxious afterwards, as opposed to being an unhealthy saturation of images and sounds, inspired a transcendent state just like a Cambodian classical dance performance? Perhaps the more striking difference between my contemporaries and I are our spiritual approaches to the art. Most Cambodians would identify as Buddhist but this Buddhism is syncretic, incorporating animism, ancestor worship, and Brahmanism into its everyday practice. Although there is much ritual surrounding Cambodian classical dance’s practice, I would argue that most dancers perform in a secular and utterly human manner that is non-transformative. Eyes only knowing the immediate human audience, make-up so very sros, or alive, but only in a limited physical sense – their execution, overpowered by nationalism and ethnocentrism, rendered a spectacle of meaningless movements. Most recently, I have become an explorer of sanatana dharma, “the eternal law”, and hope that I, with each artistic gesture, can touch Brahman – that divine matter which all things are made of, that primordial essence in which even the gods will disintegrate into, that which connects us all as living beings.

It took many pushes for me to apply for the Performing Diaspora Program. Applications came out at a time when I had just started to present performances for the Khmer Arts Salon Series, I was applying to resume my education at CalArts and UCLA, the weight of working for three organizations was making itself known, and most importantly, I was busting my brains on my first choreographic work, Robam Santhyea Vehea (Dance of Twilight Sky). Inspired by my residency in Phnom Penh where I became part of a burgeoning community of gay men who inhabited a space of neither-nor, living lives something like a silent truth in a tumultuous political landscape, as well as a lover in Siem Reap who triggered a host of memories and images, Robam Santhyea Vehea depicts two male tevea or gods who profess their love for one another before a liminal twilight sky, marrying each other before this quiet passing between night and day. With this work, I attempted to elevate my experience into the spiritual and poetic realm in which Cambodian classical dance exists, hopefully giving it more visibility and clarity in societies that do not understand it.

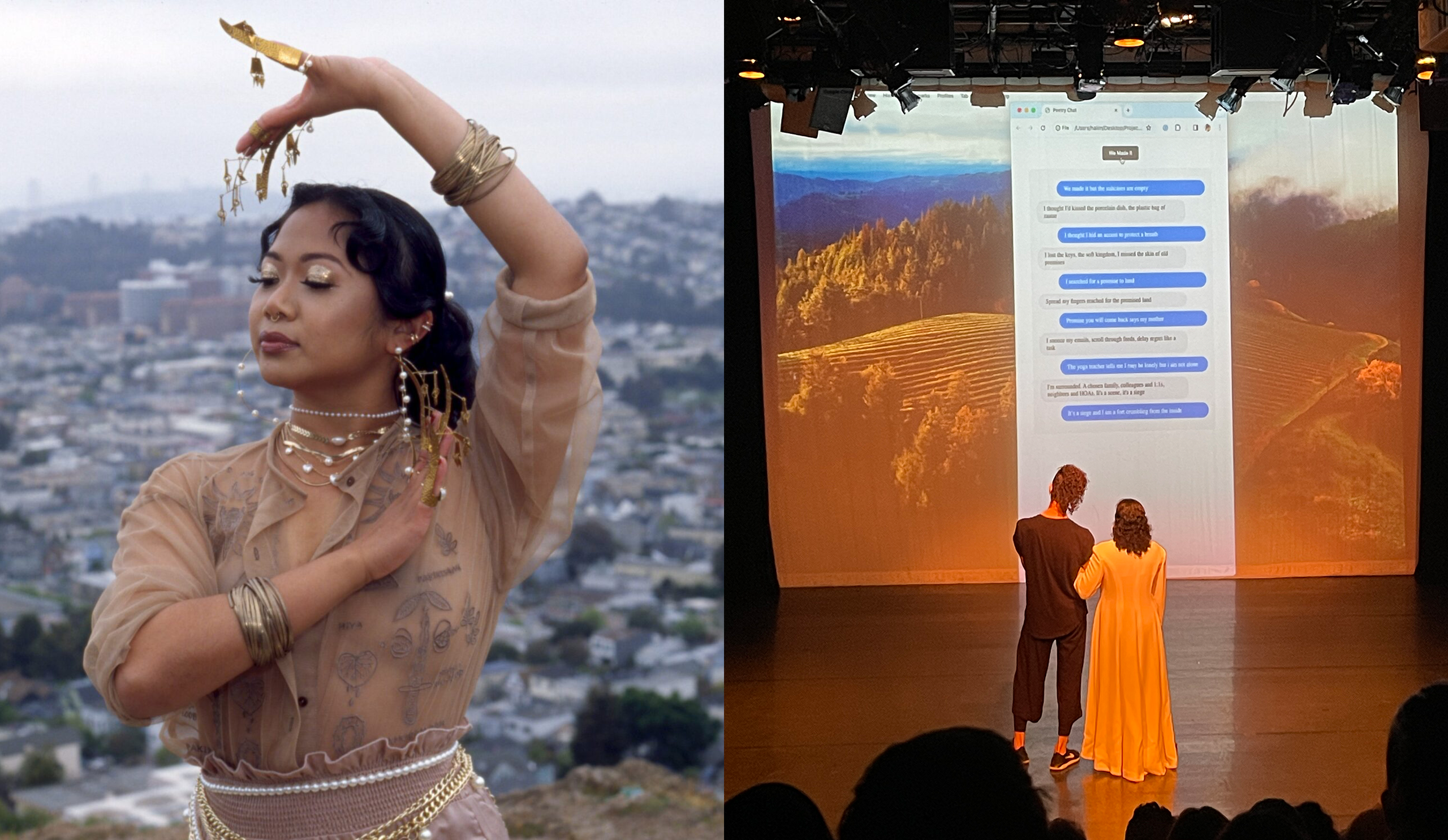

Sovann Phitu (left, Callie Ok) and Meatali (Prumsodun Ok) embrace one another before the twilight sky. Red Poppy Art House, San Francisco. Courtesy of Navin Moul.

Countless forwarded emails came into my inbox regarding the program but it wasn’t until I viewed a clip on YouTube that I was stirred into action. The video was ripped from the film, “The Royal Ballet of Cambodia”, made in the height of Cambodia’s post-colonial nationalism. The brief clip featured a scene from the story of Preah Pisnukar, legendary architect of Angkor Wat, in which his parents – a goddess condemned by Indra for stealing flowers from a painter and the man upon which the wrongdoing was committed – come to be wed (and notice that a man is playing a male role in this scene). I was unfamiliar with the melody and found it to be strikingly beautiful, and in it, a somber detachment.

I studied this video daily, listening to its every note and watching the dancers’ every gesture, and finally looked at other examples of romantic confrontations in the Cambodian classical dance repertoire. It may be a surprise to some that Robam Tamng Buon, a suite of four dances that depicts the courtship between matching pairs of gods and goddesses, is amongst some of the most sacred work in the repertoire, performed only before Roeung Moni Mekhala Ream Eyso (Drama of Moni Mekhala and Ream Eyso) which depicts the struggle that brings about the fall of rain. However, Robam Tamng Buon is the ultimate embodiment of celestial harmony: there is no struggle so these men and women can pursue each other freely, their relationship is the peaceful union of male and female forces, and there is an underlying fertility and implied regeneration and continuity in it all. There is no musical break between each dance – only a gesture of prayer that concludes each section and begins the next – and the change in melody is subtle, the narrative and tone building like light bleeding into the dark sky at dawn.

Robam Santhyea Vehea depicts a courtship and love between two divine men that is just as real and concrete as the couples in Robam Tamng Buon. However, there is a sense of just beginning and a danger surrounding the work. I employed a feminine melody that I encountered in Roeung Preah Sang (Drama of Preah Sang) in which Neang Rachana agrees to marry a nguoh who wields an unrefined staff, carrying himself with a strength and authority that is undermined by sudden cocks of the neck. He is characterized by a mask that is clown-like and negroid in its features: pitch black skin and curly hair. Neang Rachana gives her love to this man that is half-human and half-demon, crossing lines of race and class (dark skin is indicative of a peasantry tied to the land, working daily in the fields beneath an unrelenting sun) – she is later ridiculed by her fellow women, cruel voices of society, “Rachana can we see your husband? Dear gods, face of a demon!” They beat her for her social transgression and drag their husbands to witness this taboo love only to find the nguoh was actually a tevebot or divine prince named Preah Sang who had disguised himself to test his lover. But Neang Rachana, “virtuous woman, saw the golden image, beneath the nguoh’s form”: the truth behind the illusion, the substance beneath the surface all along.

I would not be surprised if this same danger lurks around the corner for me as an artist using the ultimate symbol of Cambodian culture and identity to illustrate a love between two men.

Drawing upon Cambodian classical dance’s ritual function of delivering order and harmony, the structure of Robam Tamng Buon, the somber detachment of the clip from “The Royal Ballet of Cambodia”, beliefs of reincarnation, and expounding upon the message of Roeung Preah Sang and Robam Santhyea Vehea – the virtue of love transcendent of form – I have conceived a work titled Roeung Snaih Buon (Drama of Four Loves). The characters of each dance work are unified by color, movement, and name but are unrelated to one another immediately (something I get from my literary and filmmaking training): two male tevea, Sovann Phitu and Meatali, marry one another before a liminal twilight sky; Neang Sovann Atmani gives herself to her husband, who in his absence can only take the form of memory, beneath a resilient moon; a hunter, lost in the forest after his pursuit of a deer, contemplates the touch of the sun’s golden light on his skin; Sovannapream, a Brahmin of both male and female nature (a being that is not new in the Cambodian classical dance canon), flanked by female and male devotees on either side that later dance in harmonious female-female, female-male, and male-male pairs, leads her-his community in professing their devotion and reverence for the gods who are the masters of a compassionate and transcendent love.

For Performing Diaspora, I will focus on bringing Neang Sovann Atmani vividly to life with a sweet and snaky sensuality. Memory – a landscape and form of sights and sounds, of scents and textures – almost has a physical weight and presence for this woman awaiting the return of her partner and she succumbs to it willingly, beneath her smile a silent melancholic knowing.

I am very honored and excited to be a part of this program. Much younger than my fellows, “less seasoned” and less experienced, I was touched by the curiosity and understanding – the support – visible in the eyes of Dulce, Gema, and Sherwood at the Los Angeles convening of residents. I am looking forward to all that the program has to offer, with love!

PRUMSODUN OK

- With dear friends after a performance of Robam Buong Suong Yokorn, one of the most sacred and ritualistic works of the repertoire, in which a Brahmin of male and female nature prays to the deities on behalf of the people. Courtesy of Stephane Janin.

THINGS TO READ:

Toni Shapiro-Phim’s Dance and the Spirit of Cambodia.

Rene Daumal’s Rasa, or Knowledge of the Self.

Paul Cravath’s Earth in Flower.

Share This!

More Good Stuff

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF

Prum,

your words are so poetic. You mention you are youngest, but I feel the maturity of much introspection and exploration of your art and its history. I appreciate the claiming of all of the parts of yourself. You are an inspiration and I look forward to seeing your work!

Warmly,

Shyamala

you are such a beautiful performer, writer and person! your passion leaps off the page, awakening imagination and reminding artists why we do it!

Huggles

Kyle

It’s great to hear you describe your process in words and also see how you have culled different things you have read, studied, and digested into words to help your audience. To invite your audience to understand the depth and beauty of what moves you to make art. I’m curious to see your new work and to see who will dance Neang Sovann Atmani.

Wow, what a beautiful way to share your wisdom and insight with us–you expressed yourself so sincerely and succinctly and of course drew my inquisitive self into your artistic vision. Although your particular artistic expression is completely foreign to me I feel like I walked away from your words quite a bit less ignorant and of course very excited to see Classical Cambodian Dance/Music live! Thank you.

Thank you for embracing the complexity of diaspora identity in your work! It was very refreshing to read a writing on dance that beautifully and critically engaged history, culture, race, class and gender/sexuality from a personal and political perspective. Looking forward to seeing what you produce during your residency.

Wow, what an extensive and encompassing outline of the past, present and future of your piece. It is always impressive to me to see such a clear connection between the three from an artist. And the visuals are stunning too. I can’t wait till we get in to more design conversations because I think it is going to be so exciting. I also really appreciated the reading suggestions, it will definitely help me gain more of a background and understanding of your work. I’m looking forward to hearing more.

This is awesome, I love your descriptions and writing about the act and process of dancing. Very interesting and inspiring!

It was wonderful to read something so beautiful and comprehensive…”I dance as if sculpting light and bending time…”. Your words carry power in their poetry. I am eager to see the movement to match these words.