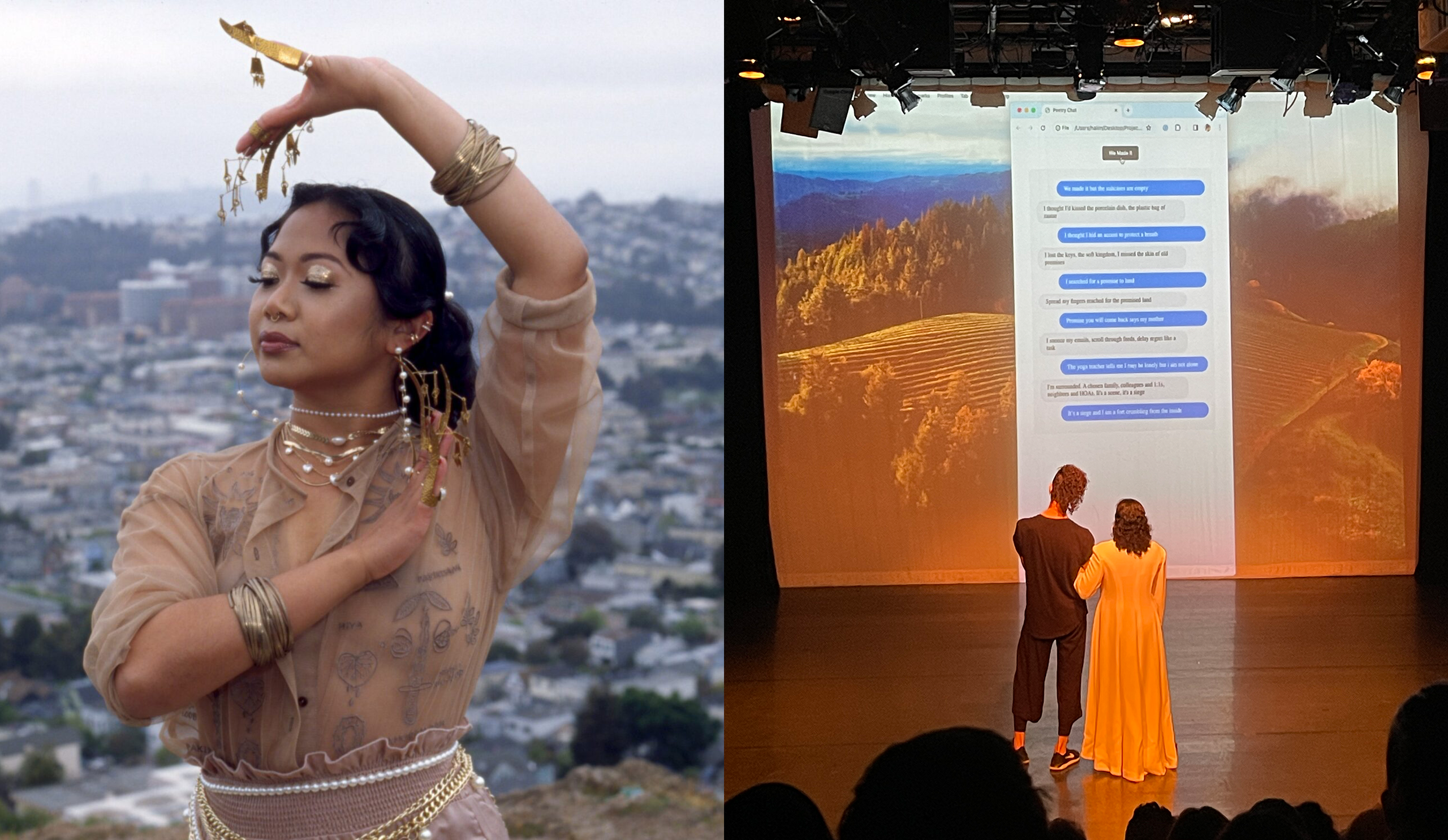

Performing Diaspora 2018 artists Melissa Lewis (顾眉) and Cynthia Ling Lee on Cynthia’s work, Lost Chinatowns. Original conversaiton on Oct 27, 2018

Melissa Lewis: I love hearing about how your work began. Can you share the story of where things started with this piece?

Cynthia Ling Lee: It all started with the search for groceries. Asian groceries, that is. All I wanted was to be able to cook my food. I had been living in North Carolina for three years and was excited to move back to California. I’d gotten a job teaching dance at UC Santa Cruz. “Yay!” I thought. “California! I’m going to have API community again!” Of course I knew Santa Cruz was a white hippie town, but I figured there would be at least a little Asian market. I was wrong.

ML: *dun dun dun…*

CLL: One afternoon I was visiting my friend and colleague, Michael Chemers, who is a dramaturg. I expressed bewilderment at the lack of an Asian grocer in Santa Cruz, and he said, “Oh, it’s no accident there are no Asian people here. There was a pogrom. They were ethnically cleansed.” (By the way, the word “pogrom” was his language—he’s Jewish.) Then Michael pulled this book off his shelf called Chinatown Dreams. It was filled with beautiful FSA-style photographs of Santa Cruz’s last Chinatown taken by George Lee.

ML: Wow.

CLL: Old men making tofu. Family portraits. Little George Ow, Jr. in his overalls with his Uncle Young holding a giant steelhead trout after fishing at the San Lorenzo River. I think it only took me a few weeks of living in Santa Cruz to learn about this forgotten history. But I meet people (white folks, usually) who have lived in Santa Cruz all their lives and who express surprise and shock that Chinese people used to live there. The erasure and invisibilization are so pervasive.

ML: Definitely. A disappearance that feels so ironic and troubling with the progressive identity that Santa Cruz champions. Are the photographic imagery or the characters you mention present in the work?

CLL: What troubles me is how Santa Cruz’s self-congratulatory progressivism exists in conjunction with this deep and convenient forgetting about its violently racist past. Santa Cruz was an epicenter for organized anti-Chinese racism in the region. And yes, much of the imagery—and the people that they portray—appear in the work in different ways. There’s a percussive chopstick/soup spoon/bowl/glass section, the rhythmic clatter of family dinners, that’s an homage to Gue Shee Lee, a matriarch of Chinatown. There’s also a passage by George Ow Jr. about the emotional experience of moving between the warm friendliness of Chinatown with its mix of yellow, brown and black folks and the cold hard concrete buildings and expressionless people of the white world outside.

ML: I appreciate how you’ve talked about Chinese identity in complexity. Culturally, nationally, linguistically, racially… what are your (Chinese) lineages and how are they informing the work?

CLL: Oh you just wanted to open that can of worms, didn’t you!? It’s always a complicated business to ask a Taiwanese person about their identity. We’ve been colonized so many times that it naturally leads to some…complexity, if not confusion.

I’m Taiwanese American, the child of immigrants to the US. More specifically, my ancestors are descended from the Hokkien-speaking Han people who first came to Taiwan as settler-colonists during the Qing Dynasty. I also supposedly have Taiwanese plains indigenous bloodlines, though my connection to those cultures and communities have been severed by colonization and genocide. Basically, I belong to the major ethnic group of China and its diaspora, the Han people; we share many cultural practices and languages. My family speaks Mandarin and Hokkien, Confucianism has informed the structure and values of my family, we practice ancestral worship, etc. But I don’t identify with China in terms of nationality.

Now, the folks that I’m paying homage to in this work were mainly Toisanese and Cantonese immigrants from the Pearl River Delta in Southern China, who lived in Santa Cruz’s Chinatowns between 1860-1955. Mostly men, because women were seldom allowed to immigrate to the United States during that time, who came before or during Exclusion.

ML: A different diaspora than yours.

CLL: Yes, a different diaspora. China is so many things, and people in the United States don’t always realize this.

ML: Definitely. There is so much oversimplification and lumping together.

CLL: I think this piece is more about coming to terms with Santa Cruz as my new home, with its long history of anti-Asian racism—which continues to affect me in subtle ways—more than an assertion of my personal identity. But that doesn’t mean audiences won’t misread it as a piece about my identity.

ML: Right. While the details and nuances live there somewhere in the air, they’re not necessarily the overt content of what’s spoken in the piece. I appreciate that. People will always have their own expectations of “legibility” .

CLL: Yes.

ML: In the glimpses I’ve seen of your work-in-process, I do feel like I’ve learned a lot from watching. Can you talk to me about your research and how that transforms within the studio?

CLL: I’ve been doing research on this work for the past two years with the support of Scott Trafton, my dear friend and the dramaturg for the work. Research has involved digging into archives and the visual record, finding a plethora of racist newspaper articles from the Santa Cruz Sentinel in the 1800s, visiting the sites where Chinese communities once were, spending time on the San Lorenzo River where many of the Chinatowns used to be. And next week I’m going to meet George Ow, Jr., a 76 year old man who grew up as a little boy in the last Chinatown.

The first incarnation of the work was a performance art piece where I built and destroyed little Chinatowns, integrating archival visual materials such as photographs, maps, censuses, and newspaper articles. I’m excited that the ephemera of these sculptures will be installed in the CounterPulse gallery as part of our show. The second incarnation, which I developed with the help of director Shyamala Moorty, sound artist Anna Friz, and dramaturg Scott Trafton, brought some of those histories and stories into more embodied form through a dance-theater solo. Now I’m trying to transform that solo into an ensemble piece.

ML: I appreciate the way you are excavating a history of violent racism and transforming it into a range of experiences for audiences. How are you folding new people into your work, currently? What has that process been like?

CLL: It’s so rich and fraught. As you know, we had an audition for the work which actively invited POC and particularly API folk to come. I have a cast of beautiful human beings and movers: Lynn Huang, Zoe Huey, and Clarissa Dyas. I don’t usually do this much research and choreographic development before folding folks into a process—and I have a history of centering collaboration and dialogue as part of my creative practice. So bringing folks in at this stage opens up a lot of challenging questions. How do I make space for people’s lived experiences and movement lineages while also honoring the histories and people invoked in the work, as well as my artistic lineages?

ML: I’m guessing your cast is not exactly of the same exact lineage as you…

CLL: There’s a range, which I’m excited about. There’s a tendency to view Chinatowns as homogeneous spaces, but they weren’t. Santa Cruz’s last Chinatown was filled with different kinds of people of color as well as poor white folks, and I think that having a cast that pushes at the edges of what folks tend to see as Asian resonates with Santa Cruz Chinatown’s diversity. Lynn is Cantonese and Taiwanese; she grew up in New York’s Chinatown. Zoe is Chinese and white; her grandfather first migrated to San Francisco from Southern China as a child in the late 1920s during Exclusion, coming and going between the two countries multiple times while building a life in the United States throughout. Clarissa is Filipina and Black. My cast has a mix of different dance training: Lynn has Graham and ballet and Chinese dance and Gyrotonics, Zoe has a pretty deep connection to a Trisha Brown lineage and to improvisation, and Clarissa is trained in various modern, contemporary, ballet techniques while influenced heavily by the choreographers she’s worked with in the Bay Area. But I must say, I feel funny summarizing their heritages and lineages. I like to let folks speak for themselves.

ML: That’s such a powerful cast.

CLL: They’re extraordinary. Sensitive and thoughtful and powerful and articulate and full of questions and heart.

ML: I imagine there are threads and commonalities, but also so much to learn about one another.

CLL: And this question of “How do I fit into the work?” is a really rich and loaded one right now.

ML: Good question! Hard question. What do you think about your role in the work?

CLL: Right now I’m trying to hold space for the fullness and complexity of everyone in the room. Trying to offer points of entry: engaging in embodied and written reflections on our own histories of migration and racialization, giving historical information and context, offering inroads into my own embodied training, which differs from those of my dancers since I have training in kathak and move in theater circles. Understanding discussion and questioning to be a deep part of this rehearsal process, which is a process of community-building. Trying to move those questions through our bodies. Being open to inviting those questions onstage.

Lost Chinatowns runs Thu-Sat, Dec 6-15 as part of Performing Diaspora 2018, a double-bill performance with Melissa Lewis (顾眉). Learn more and get tickets at counterpulse.org/performing-diaspora-2018.

Feature Photo of Lost Chinatowns by Crystal Birns

Share This!

More Good Stuff

‘Border / Line خط التماس’ by Jess Semaan and Halim Madi & ‘Sa Ating Ninuno (To Our Ancestors)’ by Kim Requesto December 5-6 & 12-13,

Unsettled/Soiled Group is a group of East, Southeast, and South Asian diasporic movers, makers, and settlers on Ramaytush and Chochenyo Ohlone land. Unsettled/Soiled Group is led by June Yuen Ting, one of CounterPulse's 2022 ARC Performing Diaspora artists and will debut Dwelling for Unsettling alongside VERA!'s Try, Hye!, Thursday through Saturday, December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022

Try, Hye! by Vera Hannush/VERA! & Dwelling for Unsettling by Unsettled/Soiled Group December 8-10 & 15-17, 2022 // 8PM PT // 80 Turk St, SF

Thanks for bringing this local history to light!